OSGi Starter

Table of Contents

- TL;DR

- Introduction

- Starting with OSGi

- Gogo

- A New Gogo Command

- API Bundle

- Provider Bundle

- JUnit Testing

- External Dependencies

- Application

- Gradle

- Git

- Release to Remote Repository

- The End

TL;DR

First, OSGi is about complex systems. It is not some secret sauce library you can sprinkle over your application and hope it will be improved. It is a pretty fundamental choice. Therefore, if you find this document too long, you likely are not in the market for OSGi. OSGi shines for complex systems and not for a hello world example.

However, if you’re too hurried to do a nice cozy read of this book then I suggest you first follow the Bndtool videos. (And even those start with a TL;DR!). This document follows the same structure. If you then want to explore things in more detail you’re welcome back!

You can skip the introduction since it is a bit of smalltalk.

Introduction

Documenting languages always seemed much more fun than elucidating OSGi. First, most developers can relate quickly to another language using examples like Hello World because the underlying concepts are so similar for most languages. However, some of the truly innovative things in OSGi are too unfamiliar to use such simplistic examples; they do require some effort from the student.

I generally addressed this large conceptual distance by making lots of pictures and diagrams, preferably with lots of animations. However, I often felt the audience drifting to thinking about what they should eat that evening instead of grasping these concepts.

I do not think I was alone in this because there are a large number of OSGi Hello World tutorials on the web where the accompanying text shows a certain disdain to OSGi developers. Why had we not explained OSGi better to them? Why were there no good tutorials explaining this simple and fantastic technology? It isn’t so hard? And with that, they made another “Hello World” tutorial that was as incomprehensible to a newcomer as the one they were rejecting.

I do take some comfort in that there were many of those tutorials, implying that these authors did not really learn that much from each other as the authors thought. Once you get OSGi, it is actually quite simple and immensely powerful. However, to get it, you actually need to understand it. And that was the rub. OSGi often feels to newcomers like a tangled mess until just before the light goes on.

One day, while preparing a course, I realized that OSGi actually has a hidden gem called Gogo. Around 2008 I’d developed a Proof of Concept (PoC) of a Command Line Interface to launch and configure an OSGi framework. It combined the idea of an object-oriented language with the ease of use of a command-line shell like bash. It can basically do anything you can do in plain Java and it is trivial to add new commands from OSGi. It even supported piping commands.

The shell never became standardized by the OSGi Alliance since we felt that there was no real need to have a standardized shell. As long as the Framework was standardized, companies could pick any shell and still have portability. However, TSH was actually quite cool and I therefore donated it to Apache Felix, where it became Gogo. Several companies picked it up and the proof of concept was transformed into a serious piece of software, becoming quite successful over time. In particular the work to adapt it to Apache Karaf improved Gogo significantly. Even Equinox, the Eclipse framework, switched to Gogo as its primary shell.

Clearly, Gogo could be used in a minimal framework without any IDE. Though I am generally in the camp of learning from first principles, I felt that just having a framework with Gogo would not suffice. After all, OSGi is not about building small programs, OSGi is about beating complexity. When the environment cannot handle complexity it is really hard to show the benefits of OSGi.

Therefore, I decided to run Gogo inside Bndtools to show the cool features of OSGi.

The bnd tool started around 2000 while I was working for Ericsson because I am lazy and distinctly disliked writing the required OSGi metadata in the manifest. Through Neil Bartlett, bnd turned into a very elegant Eclipse plugin called Bndtools. Over the past years, a large number of companies have adopted Bndtools and its sidekick Gradle.

A mature environment like Bndtools hides a lot of complexity that easily obscures important concepts. This makes it harder to see how things actually work under the hood. If it looks like magic it is hard to understand what is happening on the lower layers.

However, the advantage with Bndtools is that, out of the box, it creates correct bundles with no special setup. Since Bndtools can run OSGi frameworks in many different setups, it is easy to show all the aspects of OSGi. Most importantly, since Bndtools keeps a live framework updated of any changes in the IDE, OSGi feels like an interactive environment, i.e. similar to a Repeat-Eval-Print-Loop (REPL) that makes so many languages a joy to learn. You change some Java code and it is available inside OSGi, using the dynamic nature of OSGi to do the updates. This dynamic nature makes it worth learning OSGi & bnd in Bndtools even if you use Maven as your build system. (bnd is present in Maven plugins.)

Therefore, this book uses a combination of the Gogo shell and Bndtools to explore OSGi. It starts by installing Bndtools and a bnd workspace. A playground project is then created to run a framework with the Gogo shell. From there, we first will explore the shell itself to learn the features. After feeling comfortable with the existing commands, we add a custom ‘Hello World’ command using the OSGi Declarative Services.

We go very lightly on the basic concepts in this book. We skip all the background and instead focus on building a trivial application that has the correct scalable architecture.

The next phase is, therefore, to create an absolutely minimal workspace with an API project and a provider of this API, the architectural keystone of OSGi applications. We will explore how to test the code with plain JUnit both inside and outside an OSGi framework.

The core concept of OSGi is to build applications of reusable components. The previous sections created a reusable component so next comes the application. The application is the code that is never reusable, it only works for a specific environment and configuration.

The preferred delivery format in bnd is the executable jar. This is a JAR file that contains a launcher, a framework, and all necessary dependencies. We show how to define an application project and export it automatically to an executable JAR. Such an executable JAR can then be deployed to the target environment.

If you are a user of a bnd workspace and there is build master that maintains the low level details then you don’t need to continue with this document. It is then highly recommended to subscribe to the Bndtools mailing list.

The remainder of the document discusses how to:

-

Build the workspace with Gradle

-

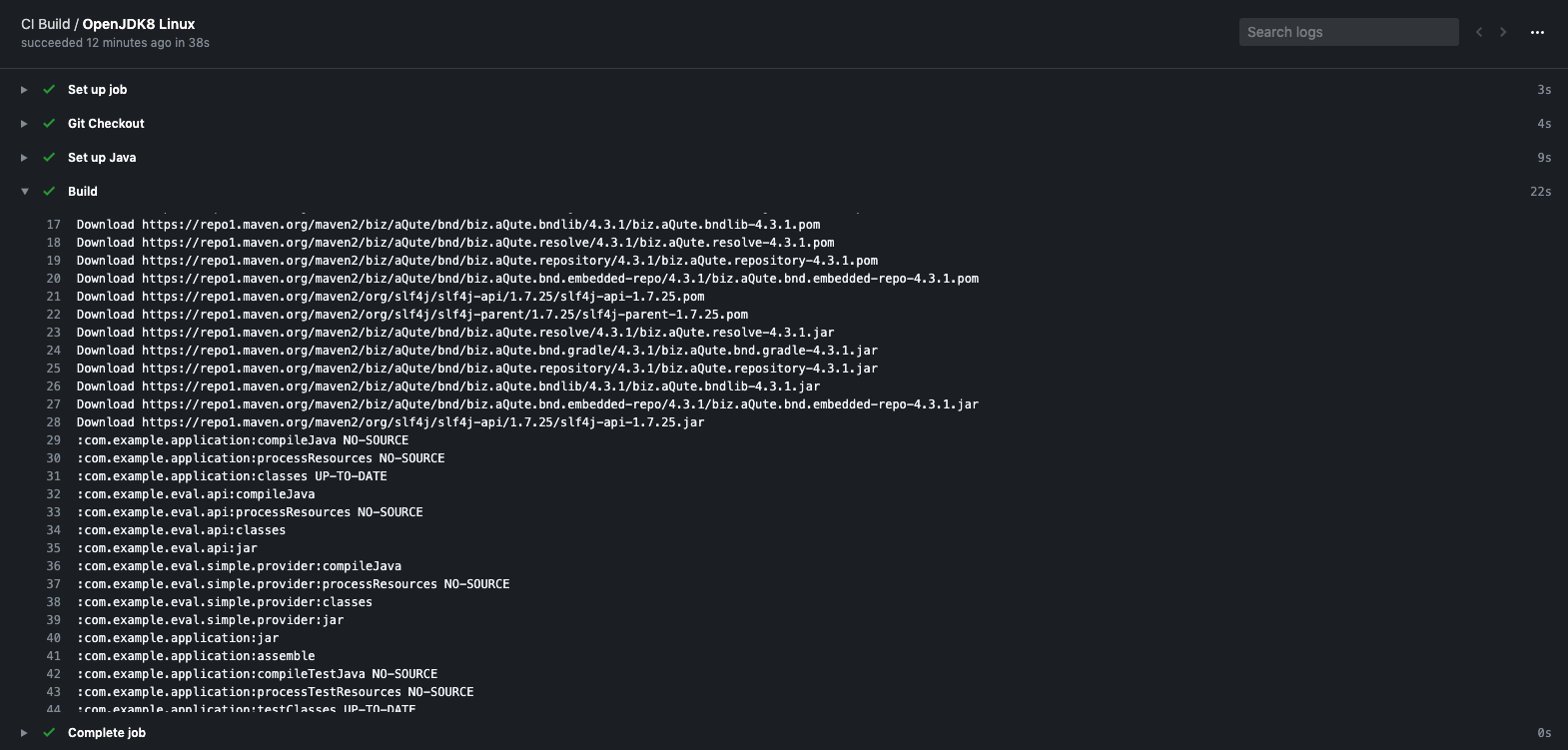

Use Github Actions to build your workspace on a remote server

-

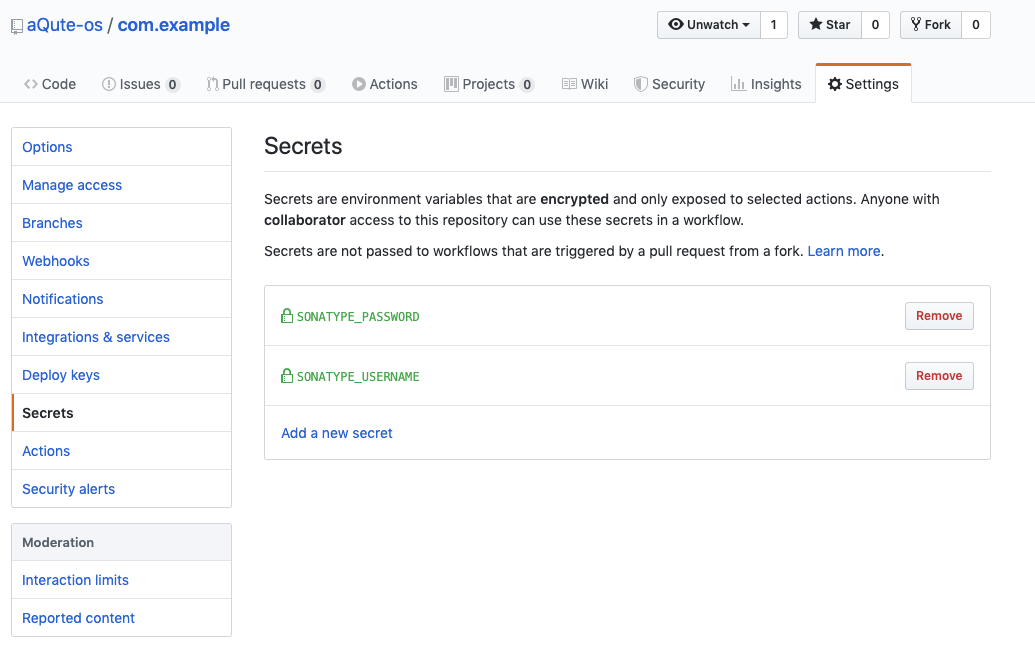

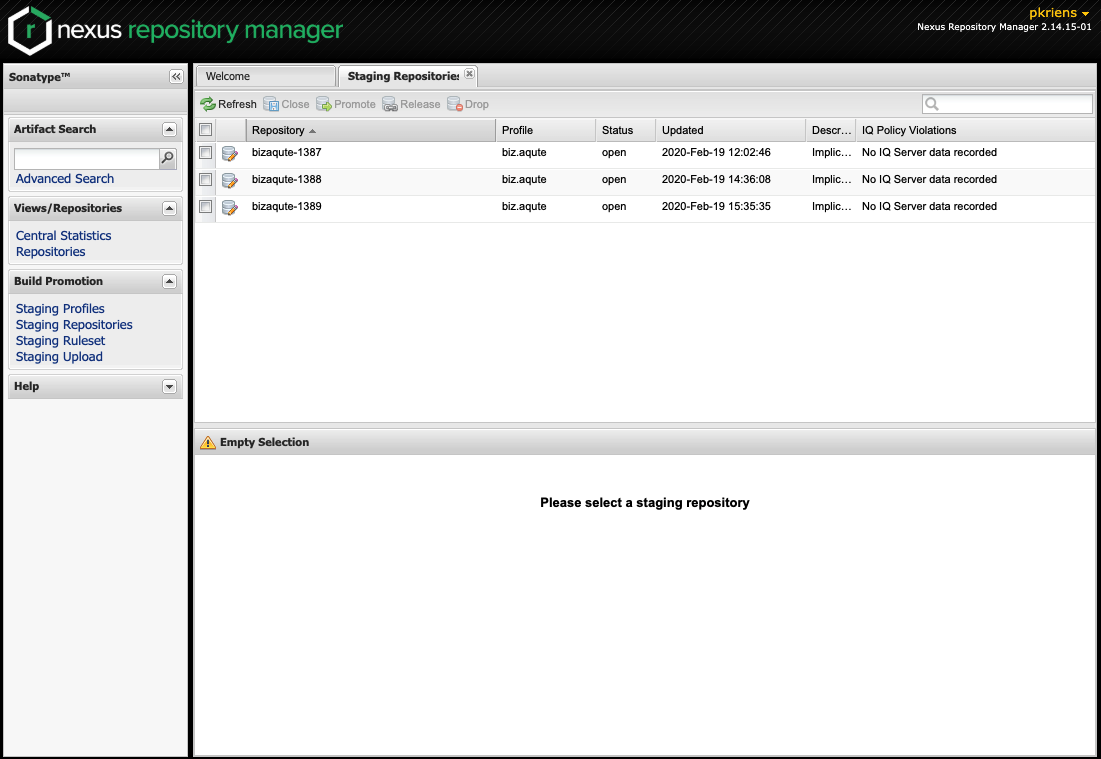

Release snapshots and releases to Sonatype Nexus repository

Enjoy! And do not forget to provide feedback to improve this document.

Starting with OSGi

TL;DR

This section will start with a hands-on deep dive into OSGi. We will install Bndtools and then create a playground project so we can explore OSGi and Bndtools in detail interactively. This kind of a crucial, and short, section to get started with Bndtools. It creates a running framework with a Gogo shell. This is very much the start level of all other chapters. So skip at your peril.

You can find a workspace with the work done in this book at https://github.com/aQute-os/com.example. Please have a Java 8 VM installed.

You can follow a short video at bndtools.org.

Installing

Install Eclipse & Bndtools. The following link can be used to find out how to install these tools.

The following sections assume that you have an empty Eclipse workspace up and running in a directory called com.example. This Eclipse workspace directory will also be used for bnd and later Git.

About Java

Once upon a time, Java was stable for years but this changed after Java 9. Nowadays, there are frequent releases. This would not be a problem if Java were kept perfectly backward compatible. However, the introduction of a module system and some tiny details make this not so. Also, tools like Eclipse and Bndtools sometimes have information that can lack the information about the latest version. Last, in the embedded world there is always a lag. For this last reason, the book is written against Java 8.

It should be possible to run everything on later Java versions but your mileage may vary. It is highly recommended to install at least one Java 8 JDK.

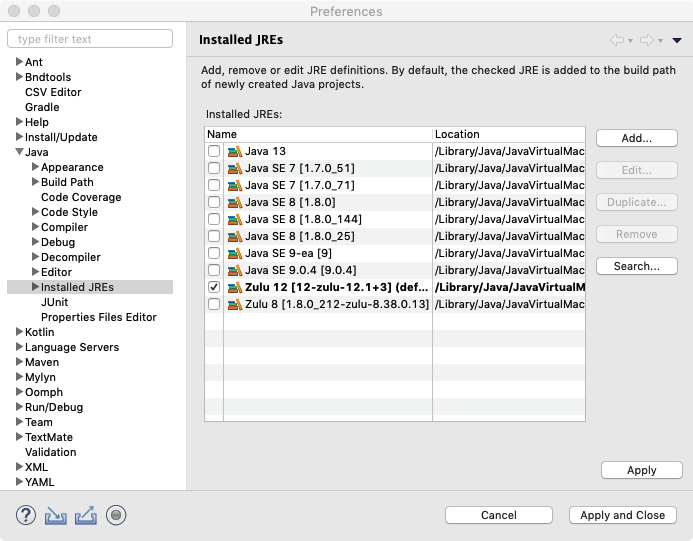

For the exercises to work, you should select a Java 1.8 JRE, which is the default in Eclipse. See Eclipse › Preferences→Java→Installed JREs

Warning: At the time of writing this document, Eclipse did not support Java 13 and 14 yet.

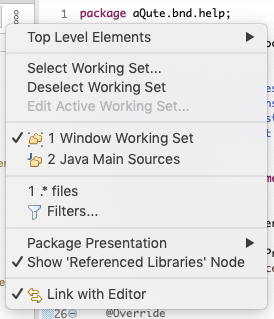

Filters in the Bndtools Explorer

By default, Eclipse filters files that start with a dot (.). Since the dotfiles are often quite interesting to look at, it is best to disable this filtering. In the Bndtools Explorer, select the little triangle or 3 dots in the top right of the view to open the menu. Then select Filters. Just enable/disable the filters you want.

Workspace Setup

The bnd tool uses the concept of a workspace. A workspace is a directory with a configuration directory (cnf) and a directory for each project. (Not nested!). The bnd workspace can overlap with the Git workspace, the Gradle workspace, and the Eclipse workspace.

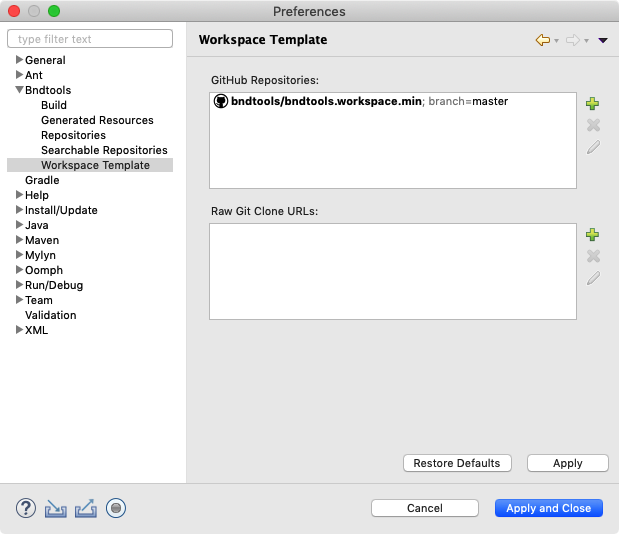

Bndtools has a preference that lists workspace templates. In this tutorial, we’ll use a minimum template.

- Preferences › Bndtools › Workspace Template

Ensure that the template bndtools/bndtools.workspace.min is in this list for the master branch. Press the Validate button to verify that you entered this template’s address correctly. You can find the content of this workspace template here:

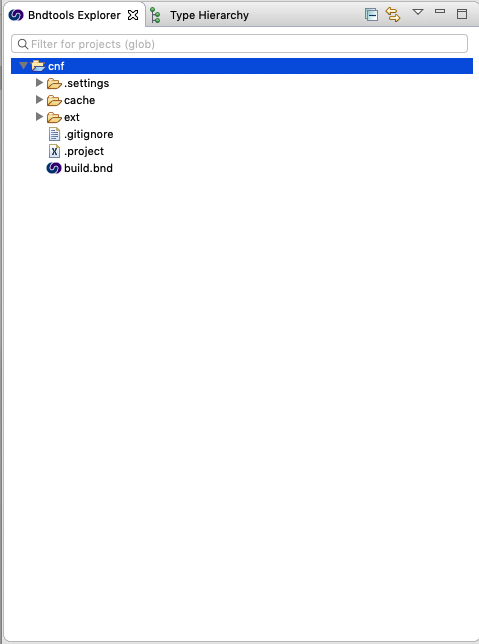

After installing the template, be sure to select the Bndtools perspective:

- Window › Perspective › Open Perspective › Bndtools

After you selected the Bndtools perspective, the explorer shows the cnf directory.

-

.settings– Eclipse settings like the compiler to be used, formatting rules, etc. -

cache– Used by bnd to cache files, must be ignored by Git -

ext– Extensions. Any properties file having an extension.bndwill be visible to all projects. -

.project– Project setup for Eclipse, do not touch -

build.bnd– A property file that contains the setup for this workspace. Anything defined in this file (or in abndfile in theextdirectory will be available to all projects.)

New Project

Create a new project to verify the setup.

- File › New › Bndtools OSGi Project

Projects can be created from templates. We are using the [[empty]](#empty) template that is part of Bndtools.

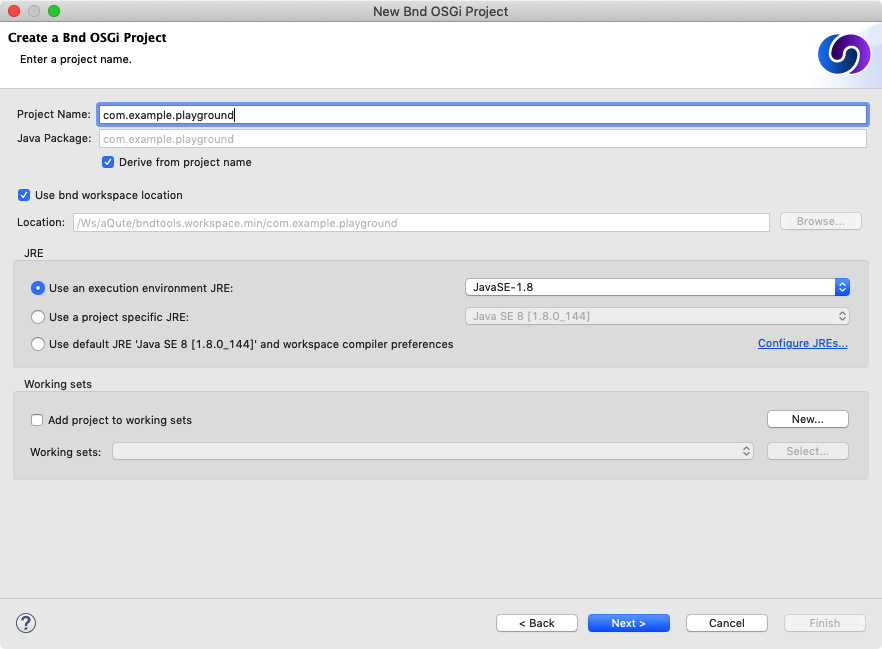

Enter the name of the project. Note that the name of the project is also the name of the bundle (a.k.a. the Bundle symbolic name). It is recommended, for this book, to use fully qualified names like com.example.playground.

Make sure the JavaSE-1.8 execution environment is selected in the popup, then click Next.

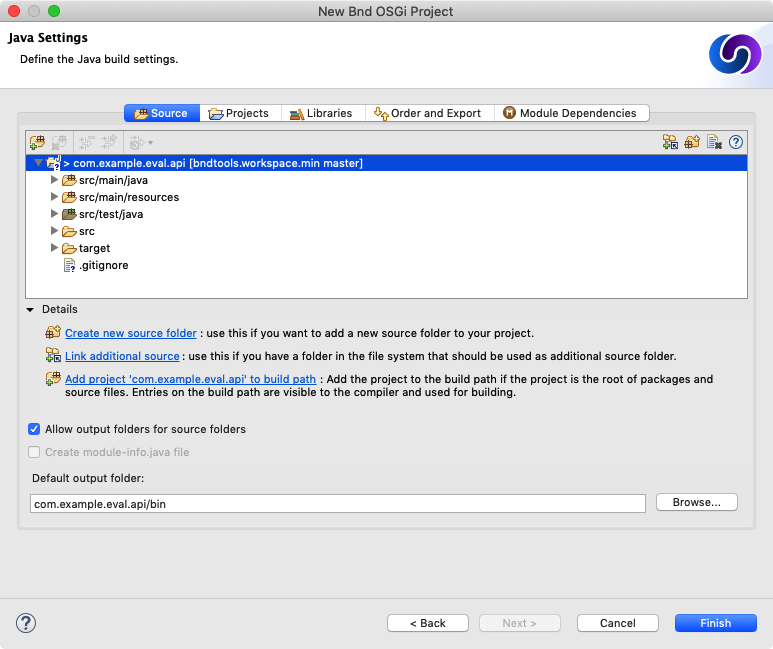

Note that the Create module-info.java file option must be disabled. If it is enabled, you’re using a >9 Java VM. In that case, make sure you know what you’re doing, it must then likely be disabled.

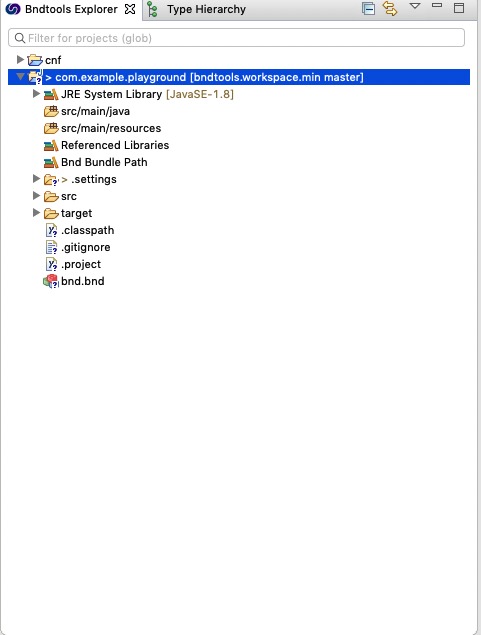

After you’ve clicked on Finish, you will see a new project.

After the project is created, you can find the following files in it:

-

JRE System Library– Links Eclipse with the correct JDK -

src/main/java– The source directory of the project. This is where the Java code goes -

src/main/resources– The resource directory of the project. This is for bundle resources like images and other files -

Bnd Bundle Path– Links Elipse to the bnd buildpath defined in thebndfile. These are the source and test dependencies for this project -

.settings– Eclipse settings like the compiler, formatting rules, etc. -

src– Top-level src directory -

target– Contains all generated files. This directory is not stored on Github -

.classpath– Project setup for Eclipse. Do not touch -

.project– Project setup for Eclipse. Do not touch -

bnd.bnd– A property file that contains the setup for this project. It inherits fromcnf/build.bnd -

…

Running

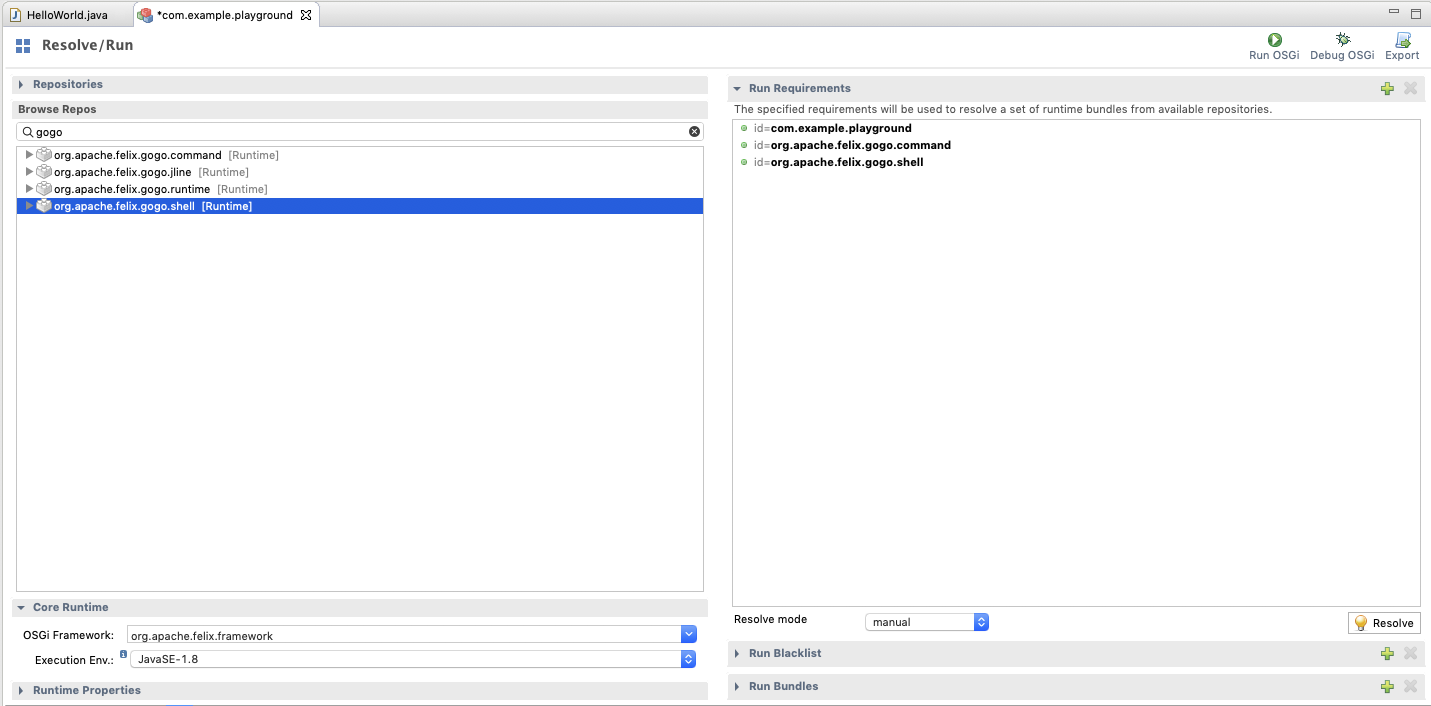

To verify that the project is correctly set up, we’ll run the Gogo shell in an OSGi framework. To keep it simple, we’ll be running an OSGi framework with the Gogo shell as the only bundles.

-

Double click on the

bnd.bndfile. This opens the bnd editor. -

Select the Run tab

-

Enter

gogoin the Enter Search string widget, this selects all bundles withgogoin their name -

Drag the

com.example.playground,org.apache.felix.gogo.command, andorg.apache.felix.gogo.shellto the Run Requirements list -

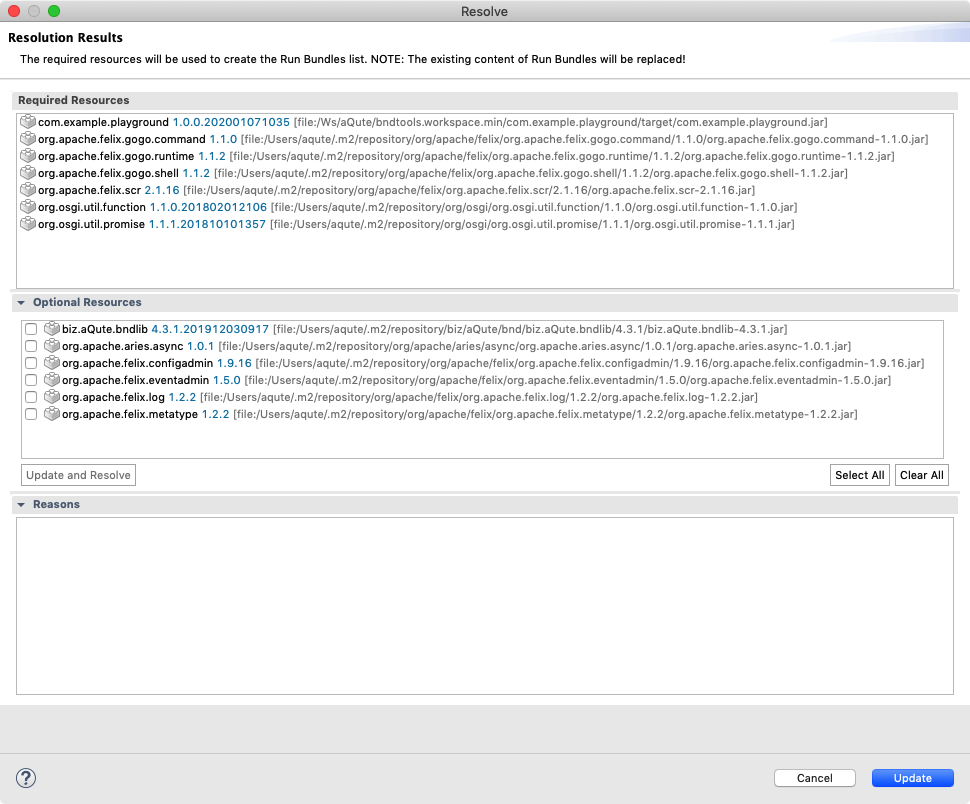

Press Resolve

-

Press Update

-

Save

-

Press Debug OSGi

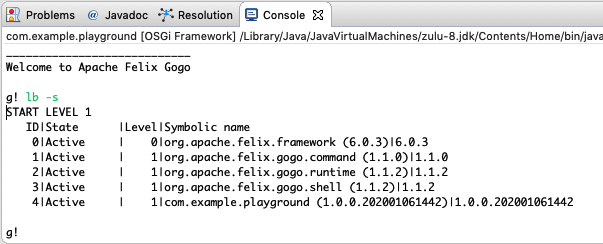

This opens the shell in the Eclipse console. You can enter lb -s to see the bundles that are running in the framework.

Summary

We’ve installed Eclipse and then created an Eclipse workspace. The Eclipse workspace was then turned into a bnd workspace from a Github template.

We then created a project as a playground for Gogo.

Gogo

TL;DR

This section explains how to use Gogo so that the remaining chapters can use Gogo to explore the examples, making much of the book very interactive.

Gogo is much more powerful than most people think. As a minimum, you should try to run the Gogo shell in the playground project and try to understand commands like help, echo, (bundle 0) headers, and s=bundle 1.

Gogo & Shells

The Gogo shell feels like a bash shell that closely interacts with the OSGi framework. Gogo was designed to allow human users as well as programs to interact with an OSGi based system through a command-line based interface, also called a shell. This shell should allow interactive and string-based programmatic access to the core features of the framework as well as providing access to functionality that resides in bundles. However, I also wanted it to be a scripting language that would work with real Java objects.

Shells can be used from many different sources, for example, the built-in Eclipse console but sometimes also from an SSH client. It is, therefore, necessary to have a flexible scheme that allows bundles to provide shell fronts based on telnet, ssh, the Java Console class, plain Java console, serial ports, files, etc. Supporting commands from bundles was made to be very lightweight to promote supporting the shell from any bundle.

In this section, we explore the usage aspect of the Gogo shell.

At Startup

When the Gogo shell starts, it prints out the following:

____________________________

Welcome to Apache Felix Gogo

g!

Commands

The most simple command is echo which works as any developer should expect.

g! echo Hello World

Hello World

Help

The org.apache.felix.gogo.command bundle provides a large number of commands. You can see those commands with the help function:

g! help

gogo:cat

gogo:each

gogo:echo

gogo:format

gogo:getopt

gogo:gosh

gogo:grep

gogo:history

gogo:not

gogo:set

gogo:sh

gogo:source

gogo:tac

gogo:telnetd

gogo:type

gogo:until

...

The list shows the scope (e.g. gogo) and the function name (e.g. grep).

The actual list is likely longer because many bundles provide additional commands.

You can get more information about a command with the help command by providing the name of the command:

g! help echo

echo

scope: gogo

parameters:

Object[]

History/Editing

In the Eclipse console, you can unfortunately not edit the commands. However, you can access the history.

g! history

1 echo Hello World

2 help

3 help echo

You can repeat a command using the bang ('!'):

g! !1

Hello World

g! !ech

Hello World

In standard terminals, you can use the cursor keys to move back and forth. Unfortunately, this not yet supported by Eclipse.

Cheat Sheet

The following is a cheat sheet of the Gogo shell. You can ignore it for now but it might be a nice reference in the future.

program ::= executable ( '|' statements )*

statements ::= statement ( ';' statement )*

statement ::= assignment | expression

assignment ::= token '=' expression

expression ::= list | map | range | closure | command | variable | ne | '(' expression ')'

command ::= target | function

target ::= expression token ( ' ' expression)*

function ::= token ( ' ' expression)*

list ::= '[' expression ( ' ' expression )* ']'

range ::= '[' expression '..' expression ( '..' expression )? ']'

map ::= '[' assignment ( ' ' assignment )* ']'

closure ::= '{' program '}'

ne ::= '%(' <numeric expression> ')'

variable ::= '$' token

token ::= <complicated>

Special characters can be escaped by quoting them (double or single quotes) or prefixing them with a backslash ('\'). Numeric expressions support common Math functions.

Tokens are parsed more or less as a sequence of characters without whitespace or any of the special characters in [](){};|&>. A special rule applies to the curly brace token ({). If it is followed by whitespace it is a separate token, otherwise it is concatenated with the rest. (Don’t ask me why, I probably suffered from some obscure use case in my mind.)

Quoting

| Quoting (double or single) is optional if the word does not contain spaces or some special characters like ‘ | ’, ‘;’, and some others. So in this case two tokens are passed to echo. Notice that we can quote the two words turning it into a single token: |

g! echo Hello World

Hello World

g! echo 'Hello World'

Hello World

Multiple Commands

You can execute multiple commands on a line by separating the commands with a semicolon (';').

g! echo Hello; echo World

Hello

World

Multiple commands can also be separated by a pipe character ('|'). In that case, the output is the input of the next command. Gogo has a built-in grep command so we can use echo to create output and grep to check the output.

g! echo Hello | grep Hello

Hello

true

g! echo Hello | grep World

Hello

false

IO Redirection

Two built-in commands cat and tac ( tac = reversed cat because it writes instead of reads) are available to provide file data and store file data. Together with the pipe operator, they replace the input and output redirection of the bash shell.

g! echo Hello | tac temp.txt

Hello

g! echo World | tac -a temp.txt

World

g! cat temp.txt

Hello

World

Built-in Commands

Gogo’s commands are methods on objects. By default, Gogo adds all public methods of the java.lang.System class and the public methods on the session’s BundleContext as commands. Instead of directly using the method names, Gogo uses the bean naming standard. That is, getHeaders() becomes headers.

This gives us access to some interesting System functions:

g! currenttimemillis

1458158111374

g! property user.dir

/Ws/enroute/osgi.enroute.examples/osgi.enroute.gogo.commands.provider

g! nanotime

1373044343558515

g! identityhashcode abc

828301628

g! property foo FOO

g! property foo

FOO

g! env JAVA_HOME

/Library/Java/JavaVirtualMachines/jdk1.8.0_25.jdk/Contents/Home

g! gc

g!

Errors

If Gogo cannot find a command, it will print a message like:

g! hello

gogo: CommandNotFoundException: Command not found: hello

This should be clear. However, sometimes it prints an Illegal Argument Exception:

g! bundle 1 headers

gogo: IllegalArgumentException:

Cannot coerce bundle(Token, Token) to any of [

(long),

(),

(String)

]

In this case, Gogo did find a method with the given name (bundle in the previous example) but it could not match the parameters to the available methods. In the example, there are three methods available:

(long) => getBundle(long)

() => getBundle()

(String) => getBundle(String)

However, it was called with getBundle(Token,Token) and therefore did not match any of the available methods.

Variables

Variables can have any name. They are set with <name>=<expr>. They are referred to by $<name>. Gogo uses variables also itself. For example, the prompt can be changed by setting a new prompt variable.

g! prompt= '$ '

$

The following variables are in use by the shell:

-

e– A function to print the last exception’s stack trace -

exception– The last exception -

prompt– The shell prompt

You can also use the ${…} pattern in a token to access variables:

g! name=World

g! "Hello ${name}"

Hello World

You can remove a variable by not providing a value:

g! foo=1

1

g! $foo

1

g! foo=

1

g! $foo

g!

Objects

Notice that none of the System commands required anything special, they are just the methods defined on the System class. That implies that the implementation has no clue about Gogo. All these commands return domain, plain, unadorned objects. We can test this because Gogo has variables that store these plain objects. We can then use those objects in the shell as commands.

g! nr = new java.lang.Integer 10

10

g! $nr doubleValue

10.0

g!

Target

The syntax feels very natural but there is something a bit tricky going on. A command is executed on a target. A target is a Java object. However, Gogo searches for a match of the command name in several places.

Literals

We’ve already used string literals. However, it is also possible to use lists and maps:

g! [1 2 3] size

3

g! [a=1 b=2 c=3] get b

\{ a=1, b=2, c=3 }

The type of the map is LinkedHashMap. Much of the original OSGi API takes a Dictionary. You can convert a literal map to a Dictionary as follows:

g! new java.util.Hashtable [a=1 b=2 c=3]

a 1

b 2

c 3

Expressions

So how do we access a specific header? A command like $nr doubleValue intValue cannot work because Gogo will see this as one command and will complain with: Cannot coerce headers(String, String) to any of [()]. The parentheses come to the rescue:

g! nr = 10

g! $nr doubleValue intValue

gogo: IllegalArgumentException: Cannot coerce doublevalue(Token) to any of [()]

g! ($nr doubleValue) intValue

10

The parentheses first calculate the expression in their inner bowels, which then becomes available as the target object for the remaining command. For example, ($nr doubleValue) returns a Double object, which subsequently becomes the target object. The intValue token is the name of the method called on this target object.

Backticks

The bash shell has this wonderful capability of executing commands to get an argument by placing backticks around a command. We can use the parentheses for the same effect, with the added benefit that the parentheses work recursively.

g! bundle = bundle 4

g! echo Bundle ($bundle bundleid) has name ((bundle ($bundle bundleid)) symbolicname)

Bundle 4 has name org.apache.felix.scr

Functions

The Gogo shell can store commands for later execution. The { and } delimiters are reserved for that purpose. We can store these functions in objects or pass them as parameters. To execute a function as a command, you should use the name of the variable without the dollar ('$') sign.

The { and } characters are not on the same parsing level as for example the [ and ]. You must separate them by spaces, otherwise, they are part of a larger token.

g! f = \{ echo Hello }

echo Hello

g! f

Hello

You can pass arguments to the function. They are named $1..$9. $0 is the command name if available. The $it macro refers to $1.

g! f = \{ echo $it }

echo $1

g! f Hello World

Hello

g! f = \{ echo $1 }

g! f Hello World

Hello

Obviously, it is not very nice that we miss the World because we only used $1. There is a magic variable called $args. This variable is list that gets expanded into separate arguments. So we can change our function to use all the arguments when the function is invoked:

g! f = \{ echo $args }

echo $args

g! f Hello World

Hello World

The $args list of arguments cannot be manipulated as a normal object as it gets expanded into its members wherever you use it.

g! prompt={ }

You can store several functions together in a file and source them:

g! source utils.gogo

...

Repeat and Conditionals

Gogo provides some built-in commands that use the functions to provide conditional and repeated execution. For example, the each command takes a collection and a function. It then iterates over the collection and calls the function with the element of the iteration.

g! each [1 2 3] \{ echo -- $it -- }

-- 1 --

-- 2 --

-- 3 --

null

null

null

We can now also use the if command:

g! l = []

g! if \{ $l isempty } \{ echo empty } \{ echo not empty }

empty

g! $l add foo

g! if \{ $l isempty } \{ echo empty } \{ echo not empty }

not empty

You can negate with the not command, which takes a function:

g! if { not {$l isempty}} { echo not empty } { echo empty }

not empty

New

You can use the new command to create new objects. The new command takes the name of a class and then the parameters for the constructor.

g! object = new java.lang.Object

Numeric Expressions

The Gogo shell has a convenient calculator for simple expressions built-in. The calculator is invoked for an expression that is enclosed by a %( and ). For example:

g! echo %(21*2)

42

Numeric expressions allow you to evaluate simple mathematical and boolean expressions. It is as far as I know completely undocumented, the parsing is flaky, and it is completely unconnected to the Gogo shell. That is, you cannot even use the variables in the Gogo shell inside an expression However, sometimes it can be a lifesaver.

Exceptions

You (and any code you call) can throw exceptions. The last exception is stored in the $exception variable and there is a built-in function e that shows the stack trace.

g! throw (new java.lang.Exception Foo)

...

g! $exception message

Foo

g! e

java.lang.Exception: Foo

at org.apache.felix.gogo.shell.Procedural._throw(Procedural.java:83)

...

You can also catch the exceptions with a try command.

g! exception = null

g! try { throw (new java.lang.Exception Foo) }

g! $exception

g!

Of course we now silently ignore the exception, which is not a good idea. So we can provide a catch function that receives the exception as the \$it variable.

g! try { throw (new java.lang.Exception Foo) } { echo ouch }

ouch

g!

Telnet Daemon

The Eclipse console is not very user-friendly for editing the command line. You can start a telnet daemon.

g! telnetd

telnetd - start simple telnet server

Usage: telnetd [-i ip] [-p port] start | stop | status

-i --ip=INTERFACE listen interface (default=127.0.0.1)

-p --port=PORT listen port (default=2019)

-? --help show help

Summary

In this chapter, you’ve learned the basics of the Gogo shell. You may wonder why so much effort is spent on learning a simple shell? Well, Gogo should be seen as the fabric of your application. We will see later that it is incredibly easy to provide first-class, well-documented commands in Gogo for every service. Having this fabric is very useful in learning and testing services.

And it is fun …

A New Gogo Command

TL;DR

Adding a new Gogo command is very easy and provides a very gentle introduction to programming in OSGi. In this chapter, we will create a component that registers a Gogo command that prints ‘Hello World’. This component is then further enhanced to use parameters and provide helpful information.

You can follow a short video at bndtools.org.

Prerequisites

This chapter assumes you have the com.example.playground project in your workspace and it is running the playground with the Gogo shell as was explained in the Starting with OSGi.

In Bndtools, everything is built and deployed all the time, after every save. Sometimes you save and this creates errors in the running framework. In this case, you can just correct the error and continue. In general, this will correct the error.

Only when you’re lost, you should restart the framework.

Creating a Project

You can create a new project with File › Bnd OSGi Project. The project will be called com.example.playground here, but you can pick your own name.

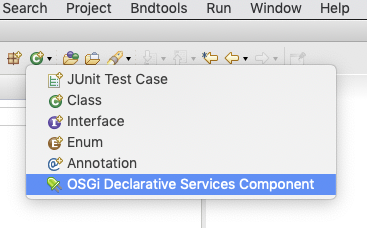

To create a component, the easiest way is to use a little C icon at the top of the window:

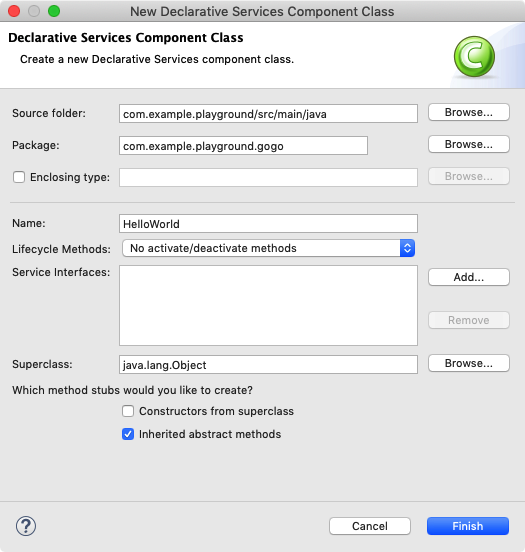

The OSGi Declarative Services Component entry opens a window for a component.

Make sure to fill in the Package and Name fields.

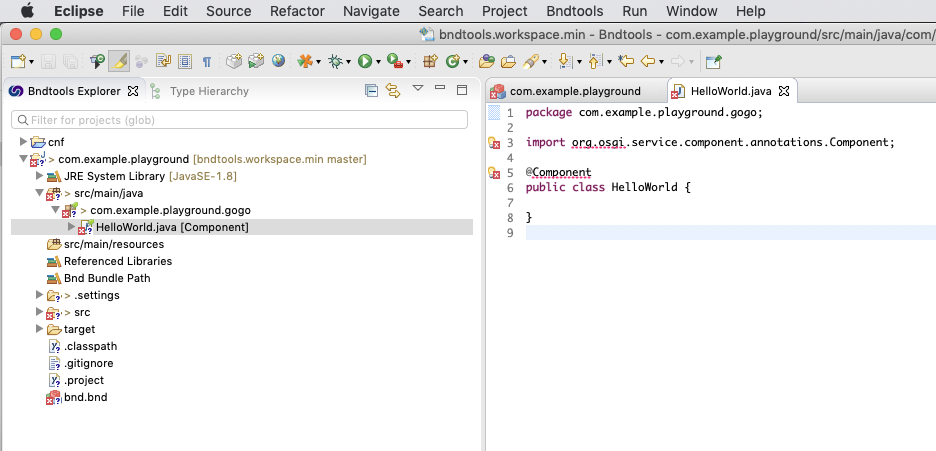

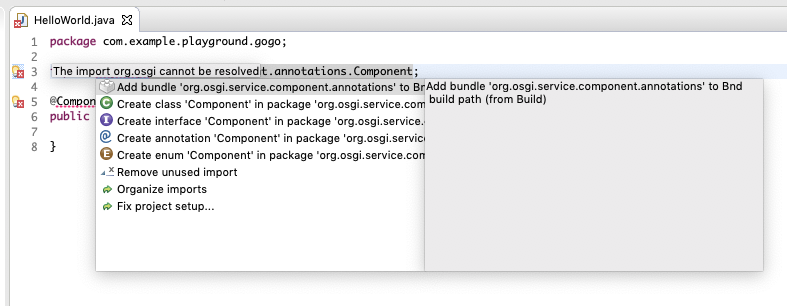

The source contains errors because we have not yet added any dependencies. Since the source uses the OSGi component annotations, the compiler cannot compile the source code. You can use the quick fix (The little yellow light bulb with the red cross) to add the OSGi annotations as a dependency.

The source now compiles and looks like:

package com.example.playground.gogo;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

@Component

public class HelloWorld {}

Bundles add commands to the shell by registering a service with the osgi.command.scope and osgi.command.function service properties. The Gogo shell detects these service properties and will register any method whose name is listed in the osgi.command.function service property. Since services could choose the same command name, the osgi.command.scope service property can be used to disambiguate the command on the command-line. Just prefix a command with the scope and a ‘:’ before the function name (no spaces).

g! scope:name

...

If a component does not implement an interface then it will not be registered as a service. Since Gogo is looking for services with the previously defined properties to register commands, it would not be able to find this “Hello World” command. Since this “Hello World” component does not implement anything, we need to make the service explicit. We use Hello class as the service type in the service() annotation method on the @Component annotation.

@Component(

property = {

"osgi.command.scope=hello",

"osgi.command.function=hello"

},

service=Hello.class

)

public class Hello {

public void hello() {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}

Running the Hello World Command

Select the bnd.bnd file, and then the Run tab. You can drag the Gogo command, the Gogo shell bundles, as well as the com.example.playground bundle into the Run Requirements list.

Then click on Resolve.

After you successfully resolved this, click the Update button. Last, save the file and click on Debug OSGi. This should start the Gogo shell in the Console view.

Using the Shell

In the shell, we can now call the function:

g! hello World

Hello World

In actual systems, the number of Gogo commands tend to get very large. The number of commands makes it hard to ensure each command has a unique name. This is the reason we had to specify the osgi.command.scope service property so commands could be disambiguated on the command line. We can now uniquely identify a command if the combination of the scope and the function name is unique.

g! hello:hello World

Hello World

System.out

In the example, we use System.out. This is ok, even if the shell is accessed via SSH or telnet. The Gogo shell redirects System.out for the duration of a command. However, using System.out makes the command only useful in a shell and the function can not really be called from other services. One of the primary goals of Gogo is to make commands very lightweight. The idea is that normal service implementations can provide commands reusing existing functions. Therefore, we can also just return the String, Gogo will then print the text.

public String hello() {

return "Hello World";

}

After you’ve made this change and saved the source, we can try it in the shell immediately; there is no need to restart the framework. Bndtools will automatically update any changed bundles. (Not restarting the framework is sometimes hard to unlearn.)

g! hello

Hello World

Arguments

Commands can also take parameters by declaring them in the prototype. For example, we can provide a name that is welcomed.

public String hello(String name) {

return "Hello " + name;

}

g! hello peter

Hello peter

Parameters can use any type they want. Gogo will attempt to coerce the given command to the proper types. For example, we could add a boolean argument to upper case the result:

public int hello(boolean uppercase, String name) {

String msg = "Hello " + name;

return uppercase ? msg.toUpperCase() : msg;

}

g! hello true peter

HELLO PETER

Flags

Linux shell commands have a convention to provide flags. Specifying, for example, -a for the ls command lists all files, including the . and .. files. You can mark a parameter with the @Parameter annotation to provide a flag.

public String hello(

@Parameter(

names={"-u", "--uppercase"},

absentValue="false",

presentValue="true")

boolean uppercase,

String name) {

String msg = "Hello " + name;

return uppercase ? msg.toUpperCase() : msg;

}

The previous code will not compile because we’re missing the bundle that provides the @Parameter annotation. You can add the following import line and then use the Quick Fix to add the org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime bundle to the build path.

import org.apache.felix.service.command.annotations.Parameter;

The names annotation field specifies an array of names that name the flag. In this case, we support the common short form of a flag (-u) and the long-form (--uppercase). The absentValue annotation method defines what value is assigned to the parameter uppercase when none of the names are used in the command. The presentValue specifies the value to use when one of the names is used in the command. The annotation fields are strings but Gogo will convert them to the field’s type. In this example, the absentValue is "false" but will be converted to the boolean false.

Since the uppercase is now a flag, we do not need to specify a boolean anymore. And since it is a flag, even the -u or --uppercase identifier is optional, if this identifier is absent Gogo will use false.

So let’s try it out:

g! hello peter

Hello Peter

g! hello -u peter

HELLO PETER

Notice that annotated parameters, like uppercase, must come before any unannotated parameters.

Optional Parameters

An option is a named parameter. Using the @Parameter annotation, we can turn a parameter in an option by specifying a set of names and a value when these names are absent. The absentValue annotation method can provide this value. There is no need to set the presentValue annotation method because we use the actual value given on the command line.

public String hello(

@Parameter(

absentValue="World",

names={"-n","--name"})

String name

) {

return "Hello " + name;

}

Since we have an absentValue, we do not need the value to be specified on the command line. So we can call the command with and without a parameter.

g! hello

Hello World

g! hello -n OSGi

Hello OSGi

g! hello --name OSGi

Hello OSGi

Adding Help

Gogo provides a help command that works out of the box:

g! help

gogo:type

gogo:until

hello:hello

scr:config

...

scr:disable

g! help hello

hello

scope: hello

We can add a @Descriptor annotations to the component to assist the help function. If you import:

import org.apache.felix.service.command.Descriptor;

And add the annotation to the method:

@Descriptor("Friendly welcome")

public String hello() {

return "Hello World";

}

Then the output of the help command has changed:

g! help hello

hello - Friendly welcome

scope: hello

You can also apply the @Descriptor annotation on the parameters.

@Descriptor("Friendly welcome command")

public String hello(

@Parameter(

absentValue="World",

names={"-n","--name"})

@Descriptor("Name to welcome")

String name

) {

return "Hello " + name;

}

g! help hello

hello - Friendly welcome command

scope: hello

options:

-n, --name Name to welcome [optional]

Property Annotation

The component properties osgi.command.scope and osgi.command.function are constructed from strings. This is an error-prone programming pattern. We used this error-prone patter to make more clear what was going on beneath the covers; it also allowed us to get started without importing the Gogo runtime bundle. However, the org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime bundle, that we use for the @Descriptor and @Parameter annotations, also contains an annotation to add service properties: @GogoCommand. This annotation cleans up the component by defining the Gogo service properties via a simple annotation.

@GogoCommand(scope="hello", function="hello")

@Component(service=Object.class)

public class HelloWorld { ... }

Summary

In this chapter, we created a Gogo command with the OSGi Declarative Services standard. We used the playground project to interactively change the initial simple command into a fully documented command with a flag and parameters.

API Bundle

TL;DR

OSGi’s primary innovation is the service registry. Services are used to decouple components/modules from each other. In OSGi, modules depend on service contracts/APIs, not on other modules as is the custom in classical module systems. Services require a contract or API. An OSGi API is a bit like a screenplay for a movie, it describes how the different actors (the service implementations) must play their role (the service interfaces). A contract is represented by an exported package in OSGi that holds the classes, interfaces, and documentation.

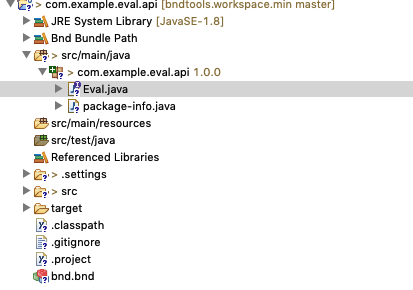

In this section, we are going to create an API for a simple expression evaluator. It will teach you how to create an API project, how to name a project, and how to navigate around inside the project. We will also explain how to export and version the API package.

You can follow a short video at API & Provider Project.

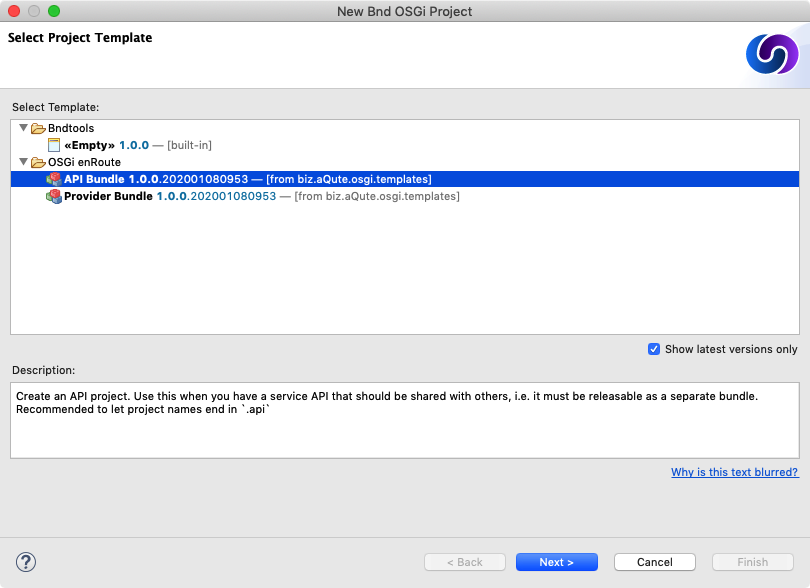

Creating an API Project

Assume, we noticed that in several projects developers evaluated expressions from a string like 5*2. They used different libraries, had different syntaxes, and they had different ways of adding custom functions. To address these issues, we created a story that there should be a service that could evaluate these types of expressions.

So let’s create an API project.

- Create a project with File › New › Bnd OSGi Project. Name the project:

com.example.eval.api

-

Use the

APItemplate. -

This template will ask for the name of the service interface. Use

Evalfor this exercise. -

Uncheck the ‘Create module-info.java file’ option if it is enabled. (This happens on Java 9 and later; it is recommended to use Java 8.)

-

Finish

-

Update the given

Evalinterface in the packagecom.example.eval.apito:

package com.example.eval.api;

public interface Eval {

double eval(String expression) throws Exception;

}

Naming

The name of this API project was not chosen at random. Over the years, a common pattern was established as a best practice to name projects.

<domain>.<workspace>.<api>\[.<provider>\].<ext>

| Part | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

domain |

|

The organization’s domain name as is common in Java |

|

workspace |

|

A unique name in the organization for the workspace/system |

|

api |

|

The API name |

|

provider |

|

A short name of the typical implementation aspect of the API |

|

ext |

|

One of the common extensions like |

The advantage of this naming scheme is that it sorts rather well. In a sorted list it puts related projects close together.

Building

Bndtools will immediately build the bundle directly after any change is saved, hence there is never a need to worry if projects have already been built. Any dependencies are also always rebuilt automatically.

Therefore, in the target directory of the com.example.eval.api project you can now find the bundle for this project. You can double click on this JAR file which will open a window with its contents. This window selects the manifest of the bundle. The manifest contains metadata for OSGi:

Manifest-Version: 1.0

Bnd-LastModified: 1578407040731

Bundle-ManifestVersion: 2

Bundle-Name: com.example.eval.api

Bundle-SymbolicName: com.example.eval.api

Bundle-Version: 1.0.0.202001071424

Created-By: 1.8.0_144 (Oracle Corporation)

Export-Package: com.example.eval.api;version="1.0.0"

Require-Capability: osgi.ee;filter:="(&(osgi.ee=JavaSE)(version=1.8))"

Tool: Bnd-5.0.0.201912100922-SNAPSHOT

Service API Package

Although a service is registered with a single interface, we should define a service in a separate package. The reason is that in anything but the most trivial services you will need support objects and multiple collaborating service interfaces. A service API is like the scenario for a role play, you have different actors (interfaces) and stage props (objects).

Therefore when we talk about a service API, we always refer to a package, although every single service is implemented in a single interface.

Exporting

The com.example.eval.api package is exported in the manifest, looking at the Export-Package header. An exported package can be used by other bundles that import it. This project was created from the API template. It automatically exports the package with the API.

You can export a package by adding an annotation to the package-info.java file in that package. This is already prepared for you by the template project.

@org.osgi.annotation.versioning.Version("1.0.0")

@org.osgi.annotation.bundle.Export

package com.example.eval.api;

You can also see that a package is exported in the Eclipse Explorer. An exported package in the explorer is exported when it is decorated with a little green + icon in the left top.

Versioning

In OSGi, a service package must be exported so that other bundles can rely on being linked to a compatible service. The purpose of versioning is to ensure that bundles that are compiled against an API are compatible with the providers of that API. Semantic versions provide the information for OSGi (and bnd) to ensure the validity of the system.

For this reason, an OSGi version has 3 parts:

major.minor.micro.qualifier

-

major– A change in this part signals full incompatibility, -

minor– A change in this part indicates that consumers are ok but providers are incompatible, -

micro– A compatible change.

Here, the API package is versioned with a version of 1.0.0 with the @org.osgi.annotation.versioning.Version("1.0.0") annotation.

Showing Off!

If you change the @org.osgi.annotation.versioning.Version("1.0.0") in the package-info.java file to version 1.2.3 and then look at the manifest by clicking on the target/com.example.eval.api.jar file. You will see that the Export-Package header is immediately updated.

If you remove the @org.osgi.annotation.bundle.Export in package-info.java then the + icon is removed from the package and the manifest will show:

Private-Package: com.example.eval.api;version=”1.2.3”

Having an @Version annotation on a non-exported package is of course not recommended. Private packages should not have versions.

Provider Type

The Eval source also shows a @ProviderType annotation. When your dependency model is based on contracts it turns out that you have two different kinds of dependencies on contracts. The provider is the bundle that is primarily responsible for the contract and the consumer is the one depends on the contract to provide it some utility. The annotations @ProviderType and @ConsumerType mark an interface’s expected implementor: either the provider or the consumer. The words consumer and provider are used because both a provider as well as a consumer can be an implementer or a user of a service interface.

Confused? Experience shows this is a difficult topic. In general, bnd will do the right thing.

Summary

We’ve now created an API project that exports a package with one interface. The project has no dependencies.

In the next chapter, we’ll create a simple provider of the com.example.eval.api API. :experimental: true :icons: font

Provider Bundle

TL;DR

In this section, we create a provider for the Eval API. We will show how to add dependencies to a project and explain the -buildpath.

You can follow a short video at Provider Project. You may also check out External Dependencies.

Providing an API

In the previous section, we created an API project for a simple expression evaluator. In this chapter, we create another project that provides an implementation for the Eval API. A bundle that has as its sole reason to provide an API is called to be a provider bundle. Any service contract can have many different providers although in general only one is selected for the runtime. For example, there are providers for the OSGi org.osgi.service.event API from Eclipse, Apache Felix, and Knopflerfish. You can compile against the OSGi API and then select one of the providers in your runtime.

Create a Provider Project

Create a project called com.example.eval.simple.provider. The simple part of the name allows us the freedom to have alternative providers of the com.example.eval.api service API. For example, we will later add a provider that uses a popular expression library from Maven Central.

Using the Provider Bundle template, you will be asked for the name for a component. Use EvalImpl for this name.

Create a Component

The template has already provided a component for you. The EvalImpl class should give the following source code:

package com.example.eval.provider;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

@Component

public class EvalImpl { }

Dependencies

The next step is to implement the Eval interface from our API project. It is time anyway to dive deeper into how bnd handles the build path.

To compile the code, the compiler needs to have a build path, a set of bundles that provide the APIs to compile against. This build path is defined in the bnd.bnd file in every project.

If you open this bnd.bnd file and select the Source tab you see it is currently empty.

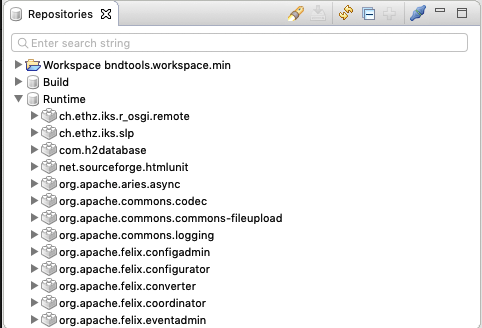

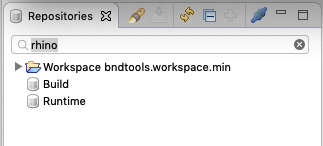

Repositories

The workspace has several repositories, repositories are a collection of bundles. If you look at the bottom-left of the screen (in the Bndtools perspective) you can see the current repositories of the workspace.

In the current workspace there are three repositories configured:

-

Workspace – Contains all the bundles from the projects

-

Build – Bundles intended to be used in the build only. E.g. API, test, etc.

-

Runtime – Bundles for the runtime

The repositories are defined in the cnf project, look in the ext directory for their definition files. We will not discuss the details here. However, bnd has an extremely flexible repository model and supports out of the box Maven repositories, P2 repositories /target platforms, and OSGi XML repositories.

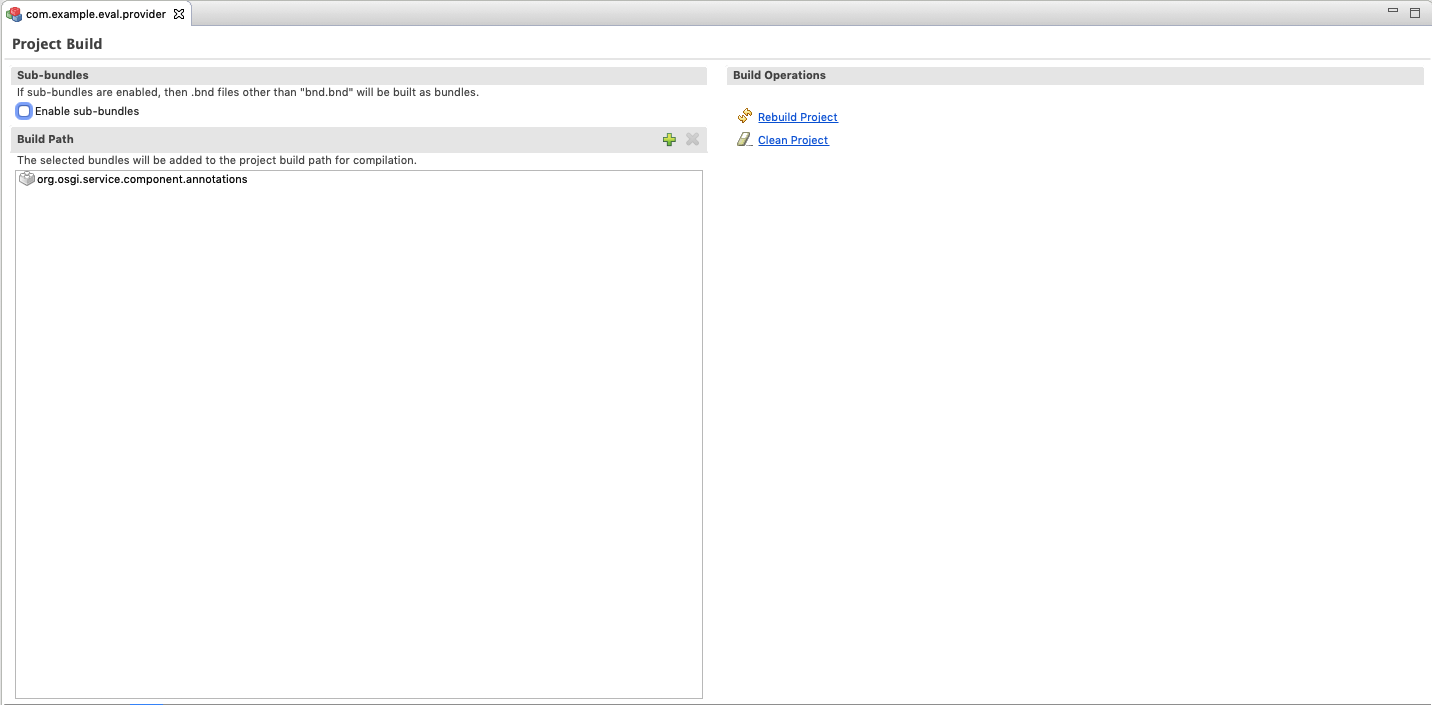

Build Path

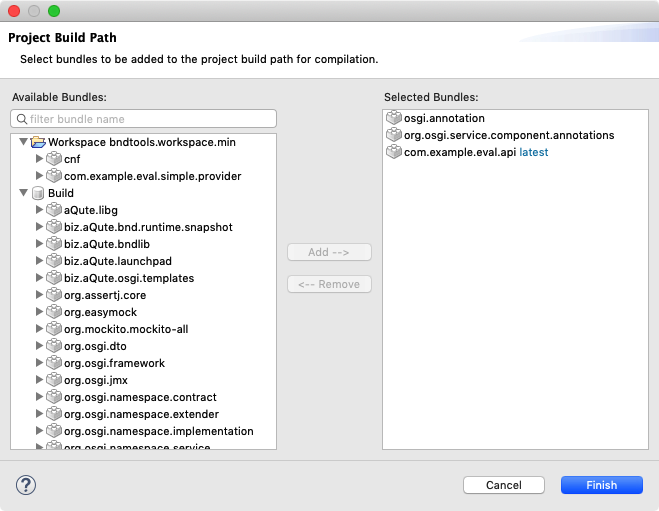

The build path dependencies of a bnd project are defined in the bnd.bnd file. We can, therefore, control the build path through the build path editor. Double click on the bnd.bnd file and select the Build tab.

As you can see, the org.osgi.component.annotations bundle is already listed. To add another dependency, click on the + and then swipe the com.example.eval.api bundle from the left to the right (or click the Add if you’re not into swiping). If you’re looking for a specific bundle then you can filter them by symbolic name. Type the name in the filter text box to limit the entries that match.

Press Finish and save the bnd.bnd file because otherwise there is no effect.

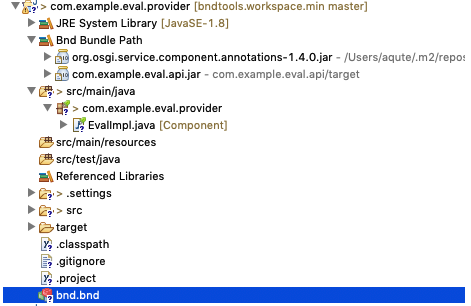

When you save this file, Eclipse will add all bundles on the build path to its internal compiler path. If you look in the Bndtools Explorer, open the project, then you should see an item called Bnd Bundle Path. You can open this entry and beneath it, you will see all build path entries. Each entry is also possible to open, it allows you to inspect the classes that are contributed to the compiler.

Implementing Eval

You can now go back to the EvalImpl class and implement the Eval interface.

@Component

public class EvalImpl implements Eval {}

Just select the Eval name (which is red underlined) and click Control-1, select Import 'Eval' (com.example.eval.api). This will take care of the import. Don’t forget to save it!

Alas, we got rid of the import error but in place of this error, we now get a red underlined EvalImpl class. The problem is that we need to provide the eval method, as prescribed by the Eval interface that it now implements. Let’s keep it as simple as possible while still doing something not utterly useless:

@Component

public class EvalImpl implements Eval {

Pattern EXPR = Pattern.compile( "\\s*(?<left>\\d+)\\s*(?<op>\\+|-)\\s*(?<right>\\d+)\\s*");

@Override

public double eval(String expression) throws Exception {

Matcher m = EXPR.matcher(expression);

if ( !m.matches())

return Double.NaN;

double left = Double.valueOf( m.group("left"));

double right = Double.valueOf( m.group("right"));

switch( m.group("op")) {

case "+": return left + right;

case "-": return left - right;

}

return Double.NaN;

}

}

Ok, ok, calling it simple might still give it too much credit but we’re not here to learn parsing. At least it has (some) error handling! Notice that we can only handle trivial additions and subtractions of constants.

Imports

It is about time now to take a look at what our bundle really looks like. Double click on the target/com.example.eval.simple.provider.jar file. This opens the JAR Editor. Select the Print tab, look at the IMPEXP section.

[IMPEXP]

Import-Package

com.example.eval.api {version=[1.0,1.1)}

The reason we import the minor range ([1.0,1.1)) is that the Eval interface was annotated with the @ProviderType and we do implement this interface. Because we implement a provider interface, bnd assumes this bundle is a provider of the com.example.eval.api API and therefore must import the package with a minor range. If the contract changes in any way, we need to make a new version of this provider bundle.

Note: The concepts of provider and consumer of APIs seem hard to understand. Fortunately, bnd handles it all quite well. Trust us. :-)

Gogo Command

Making a service a Gogo command is a good way to play with the services that are being developed.

Add org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime to the -buildpath in the bnd.bnd file.

-buildpath: \

osgi.annotation,\

org.osgi.service.component.annotations,\

com.example.eval.api;version=latest,\

org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime

-testpath: \

osgi.enroute.junit.wrapper, \

osgi.enroute.hamcrest.wrapper

Then add the @GogoCommand annotation to the EvalImpl class.

@GogoCommand(scope="simple", function={"eval"})

@Component

public class EvalImpl implements Eval {...}

Running in the Playground

Open the bnd.bnd file of the com.example.playground project we created in the starting section. Select the Run tab. In this tab you can add the com.example.eval.simple.provider bundle to the initial requirements. You should then Resolve. The calculated list of bundles should look something like:

org.apache.felix.gogo.command

org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime

org.apache.felix.gogo.shell

com.example.playground

org.apache.felix.scr

org.osgi.util.function

org.osgi.util.promise

com.example.eval.api

com.example.eval.simple.provider

The resolver that we used is the secret weapon of OSGi. It searches the repositories, including our own code, for bundles that can work together. Each bundle contains metadata that describes what requirements it has to the outside world and what capabilities it can provide. In the end, the resolver creates a set of bundles where all their requirements are satisfied. Or it gives up …

Notice how the resolver automatically added the com.example.eval.api bundle. It noticed that this was required by the com.example.eval.simple.provider bundle.

You should Finish the resolver and save the bnd.bnd file.

If the framework was still running, the new bundles will automatically be added. We should then immediately be able to run the command:

g! eval 1+2

3.0

Summary

In this section, we created a provider for the com.example.eval.api API. We used the Provider template to create an EvalImpl component. We extended the build path to contain the API project and wrote a simplistic implementation.

We then tested the implementation with a Gogo command in the playground.

JUnit Testing

TL;DR

In this section, we will create a whitebox JUnit test for our provider implementation. This test will not depend on OSGi. It is a goal in OSGi projects to make the components testable without the overhead of an OSGi framework. These JUnit tests are very cheap; using them extensively saves a tremendous amount of time in later phases of the development process. JUnit tests are always run before code is released and when they fail, they prohibit the release of the project.

JUnit tests can also contain launchpad, a bnd library to test with an OSGi framework present.

Testing is one of those chores a developer has to do, not as much fun as some deep algorithmic code. However, it is likely one of the most effective ways to spend your time.

This section is not needed if you’re familiar with JUnit and launchpad.

JUnit

A provider should always have unit tests. Unit tests are white box tests. The test knows about the implementation details and it can even see aspects of the components that are not part of the public API.

The Provider Bundle template provided us with a template for the test class: EvalImplTest in the test folder. This class is set up to run a JUnit 4 test:

package com.example.eval.simple.provider;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertNotNull;

import org.junit.Test;

import com.example.eval.simple.provider.EvalImpl;

public class EvalImplTest {

@Test

public void simple() {

EvalImpl impl = new EvalImpl();

assertNotNull(impl);

}

}

The test folder is special. No code from the test folder should not end up in our bundle, nor should any of its dependencies be counted as imports. For this reason, the test folder is compiled with the -buildpath and the, -testpath. bnd guarantees that no test code, nor any of its dependencies in the -testpath, can accidentally end up in the bundle.

The template has already set up the -testpath with the JUnit dependencies. You can click on the bnd.bnd in the com.example.eval.simple.provider project, select the Source tab:

#

# com.example.eval.simple.provider PROVIDER BUNDLE

#

-buildpath: \

osgi.annotation,\

org.osgi.service.component.annotations,\

com.example.eval.api;version=latest

-testpath: \

osgi.enroute.junit.wrapper, \

osgi.enroute.hamcrest.wrapper

So let’s evaluate a simple expression:

package com.acme.prime.eval.provider;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertEquals;

public class EvalImplTest {

@Test

public void testSimple() throws Exception {

EvalImpl t = new EvalImpl();

assertEquals( 3.0, t.eval("1 + 2"), 0.0001D);

}

}

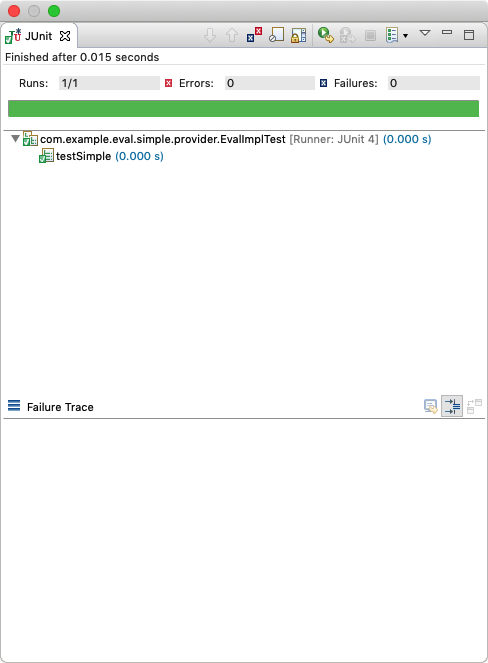

You can run the test by selecting the class name (EvalImplTest) or the method name (testSimple), call up the context menu, and select RunAs › JUnit Test. Do not select RunAs › Bnd OSGi Test Launcher (JUnit)

To run JUnit tests you can select the project in the explorer, the test folder, a package, a class, or a method and call up the context menu and then RunAs › JUnit Test. It will then run all tests selected beneath that level.

Debugging

Since most code does not run the first time, we need to debug as well. You can set a breakpoint by double-clicking in the margin where you want the breakpoint to happen. A blue dot then appears. Just select the test method you want to run and do Debug As › JUnit Test.

The JUnit pane has many buttons that allow you to rerun tests, an incredibly powerful tool.

Launchpad

Launchpad is bnd library that makes it easy to test OSGi code in a normal plain JUnit environment. To use Launchpad, make sure to add the following entries to your -testpath in the bnd.bnd file:

-testpath: \

biz.aQute.launchpad,\

org.osgi.framework,\

slf4j.api,\

slf4j.simple,\

org.osgi.resource,\

org.osgi.dto,\

org.osgi.util.tracker,\

com.example.eval.api, \

osgi.enroute.junit.wrapper, \

osgi.enroute.hamcrest.wrapper

Also add the following runbundles:

-runbundles: \

com.example.eval.api;version=snapshot,\

org.apache.felix.scr,\

org.osgi.util.function,\

org.osgi.util.promise,\

org.apache.felix.gogo.command,\

org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime,\

org.apache.felix.gogo.shell

Change your test class to the following:

@RunWith(LaunchpadRunner.class)

public class EvalImplTest {

static LaunchpadBuilder builder = new LaunchpadBuilder().bndrun("bnd.bnd");

@Service(service = Eval.class)

EvalImpl eval;

@Service

Launchpad launchpad;

@Test

public void simple() throws InvalidSyntaxException {

assertNotNull(eval);

launchpad.report();

}

}

Making Bundles

The Launchpad object contains a special bundle builder. It provides the same capabilities that bnd already has when it creates bundles. You can use all the facilities that you can use in the bnd.bnd file: Export-Package, Import-Package, -includeresource, etc.

The following example shows how to create a bundle with a special header.

@Test

public void bundles() throws Exception {

Bundle b = launchpad.bundle()

.header("FooBar", "1")

.install();

String string = b.getHeaders()

.get("FooBar");

assertTrue(string.equals("1"));

}

Interaction with Services

Clearly, the best part of Launchpad is that you can actually use real services and do not have to mock them up. Many a test seems to mostly test their mocks.

With Launchpad, a real framework is running. You can inject services or register services.

In the following example, we register a service Foo and then verify if we can get it. We then unregister the service and see that it no longer exists.

interface Foo {}

@Test

public void services() throws Exception {

ServiceRegistration<Foo> register = launchpad.register(Foo.class, new Foo() {

});

Optional<Foo> s = launchpad.waitForService(Foo.class, 100);

assertTrue(s.isPresent());

register.unregister();

s = launchpad.waitForService(Foo.class, 100);

assertFalse(s.isPresent());

}

The waitForService methods take a timeout in milliseconds. Their purpose is to provide some leeway during startup for the system to settle. If a service is expected to be registered then the getService() methods can be used.

Injection

You can declare fields with the @Service annotation and they are injected. However, not all tests use the same types so you can also injection manually. The injection can also happen as often as you want.

@Test

public void inject() throws Exception {

ServiceRegistration<Foo> register = launchpad.register(Foo.class, new Foo() {

});

class I {

@Service

Foo foo;

@Service

Bundle bundles[];

@Service

BundleContext context;

}

I inject = new I();

launchpad.inject(inject);

assertTrue(inject.bundles.length != 0);

register.unregister();

}

Hello World

Although the of a Bundle-Activator is not recommended, they are singletons, a Bundle-Activator can be very useful in test cases. With Launchpad it is not necessary to make a separate bundle, we can make a bundle with an inner class as an activator.

We first define the Bundle Activator as a static public inner class of the test class:

public static class Activator implements BundleActivator {

@Override

public void start(BundleContext context) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

@Override

public void stop(BundleContext context) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Goodbye World");

}

}

The Launchpad class contains a special Bundle builder. This bundle builder is based on bnd and can do everything that bnd can do in a bnd.bnd file. In this case, we add the Bundle Activator and start it.

@Test

public void activator() throws Exception {

Bundle start = launchpad.bundle()

.bundleActivator(Activator.class)

.start();

}

When the test is run the output is:

Hello World

Goodbye World

Tidbits

Launchpad is incredibly powerful but the class loading model used is quite tricky. The manual of Launchpad goes into some of these details. If you want to use Launchpad in anger, make sure you have read this section.

External Dependencies

TL;DR

In this section, we create another provider for the Eval API using Javascript via the Mozilla Rhino interpreter. We will show how to add a dependency from Maven Central to your build and use it in a project.

You can follow a short video about External Dependencies

Rhino

Rhino is a Javascript interpreter that we can use to evaluate the expressions a bit more professional than the regular expression hack we used in the com.example.eval.simple.provider. Looking at the Rhino documentation, we can evaluate an expression with the following method:

@Override

public double eval(String expression) throws Exception {

Context cx = Context.enter();

try {

Scriptable scope = cx.initStandardObjects();

Object result = cx.evaluateString(scope, expression, "?", 1, null);

if (result instanceof Number)

return ((Number) result).doubleValue();

return Double.NaN;

} finally {

Context.exit();

}

}

Create a Rhino Provider Project

Create a project called com.example.eval.rhino.provider. It should be clear now why we chose the naming pattern. All projects related to the Eval API are now close together in the Bndtools/Package explorer.

Using the Provider Bundle template, you will be asked for the name for a component. Use RhinoEvalImpl for this name.

Create a Component

The template has already provided a component for you. The RhinoEvalImpl class should give the following source code:

package com.example.eval.provider;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

@Component

public class RhinoEvalImpl { }

You can modify it to:

package com.example.eval.rhino.provider;

import org.mozilla.javascript.Context;

import org.mozilla.javascript.Scriptable;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

import com.example.eval.api.Eval;

@Component

public class RhinoEvalImpl implements Eval {

@Override

public double eval(String expression) throws Exception {

Context cx = Context.enter();

try {

Scriptable scope = cx.initStandardObjects();

Object result = cx.evaluateString(scope, expression, "?", 1, null);

if (result instanceof Number)

return ((Number) result).doubleValue();

return Double.NaN;

} finally {

Context.exit();

}

}

}

External Dependencies

This code will have errors. You should now be able to add the missing Eval interface by adding the com.example.eval.api project to your -buildpath in the bnd.bnd file via the Build tab.

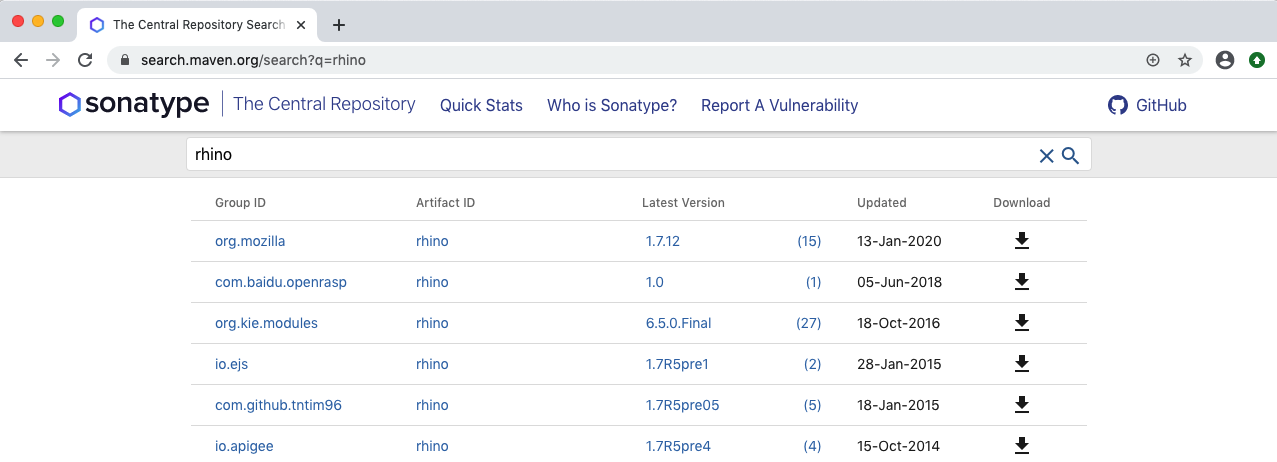

The com.example.eval.api was in the Workspace repository, so we could find it, but the Rhino dependencies cannot be found in the repositories. This mechanism, therefore, does not work here.

However, we can find this dependency on Maven Central:

Searching for external dependencies on Maven Central is not always easy. Sadly, many organizations prefer to wrap a bundle when it lacks a feature. This means that finding the right bundle is sometimes wading through a lot of dead bundles. However, in this case, it is clear that at the time of this writing the org.mozilla:rhino:1.7.12 is GAV coordinates of the proper artifact.

A GAV has the following syntax:

GAV ::= groupId ‘:’ artifactId ( ‘:’ extension ( ‘:’ classifier )? )? ‘:’ version

The groupId is an organizational identifier. For example, all bnd code is in the biz.aQute.bnd group. The artifactId identifies the program name. The version should be clear. One note, in bnd, versions have a proper syntax, that is, 1.2.3 is exactly the same version as 01.02.03. Maven uses the version string as an opaque identifier and sees 01.02.03 as distinctly different than 1.2.3.

Maven Bnd Repository

The workspace template we used uses two repositories that are defined in the cnf/ext/defaults.bnd file. These repositories are linked to Maven Central. The Build repository contains artifacts that should never be used in runtime. The Runtime repository can be used to compile against or used in runtime.

We can add the Rhino GAV, org.mozilla:rhino:1.7.12, to the Runtime repository. The GAVs for the Runtime repository are stored in the cnf/ext/runtime.mvn file. If you open this file, it should look similar to:

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.framework:6.0.3

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.framework.security:2.6.1

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.configadmin:1.9.16

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.configurator:1.0.10

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.coordinator:1.0.2

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.eventadmin:1.5.0

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.fileinstall:3.6.4

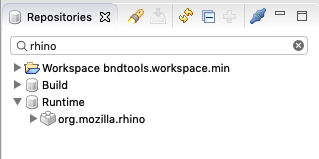

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.http.servlet-api:1.1.2

org.apache.felix:org.apache.felix.http.jetty:4.0.14

As you can see, these mvn files are a list of GAVs. You can add the org.mozilla:rhino:1.7.12 GAV in this file and save it. This will automatically update the repositories. Therefore, you can now search in the repositories view.

We can now go to the bnd.bnd file and select the Build and add the org.mozilla.rhino dependency on the -buildpath. This will add it to the Bnd Bundle Path in the Bndtools Explorer.

In the RhinoEvalImpl.java source code we can now do the imports and make it compile correctly.

Gogo Command

To exercise this provider, we want to make it a Gogo command. We therefore need to add org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime to the -buildpath in the bnd.bnd file. The source of the bnd.bnd file should look like:

-buildpath: \

osgi.annotation,\

org.osgi.service.component.annotations,\

com.example.eval.api;version=latest,\

org.apache.felix.gogo.runtime

-testpath: \

osgi.enroute.junit.wrapper, \

osgi.enroute.hamcrest.wrapper

Then add the @GogoCommand annotation to the EvalImpl class.

@GogoCommand(scope="rhino", function={"eval"})

@Component

public class RhinoEvalImpl implements Eval {...}

Running in the Playground

Open the bnd.bnd file of the com.example.playground project that we created in the starting section. Then select the Run tab. In this tab you can add the com.example.eval.rhino.provider bundle to the initial requirements.

Select auto in the popup menu on the left side of the Resolve button. The resolve will then automatically happen on saving the file.

Save the file.

If the framework was still running, the new bundles will automatically be added. We should then immediately be able to run the command:

g! rhino:eval 1+2

3.0

Summary

In this chapter we created a second provider to the Eval interface. For this provider, we had to find an external dependency on Maven Central. We found the Mozilla Rhino Javascript interpreter. This dependency was added to the runtime.mvn file. After saving this file, it became available to add it to the -buildpath.

Last, a @GogoCommand annotation was added to the component to be able to test it in Gogo.

Application

TL;DR

Bndtools supports executable jars. These are JARs that contain all dependencies and can directly be executed by the Java VM. This section outlines the role of the application project and shows how you can create such an executable JAR.

You may also want to take a look at Executable JARs.

Application Bundle

In OSGi, an application is a bundle that acts as the root of a runtime assembly. The application is a bundle that is specific for some complete end-user functionality. A very important aspect of an application is that it is a leaf node in a dependency graph, it must never required by any other bundle. In a perfect system, this is the only part that is not reusable.

For non-application bundles, it is recommended to minimize dependencies because every dependency makes it harder to use that bundle in different applications. However, the application bundle is free from these constraints. An application can be a web application but also for a specific device configuration. It is the thing that you deploy for your customers.

Applications should only require other code and rarely include any code since that code can never be reused. We, therefore, create a new project that is dedicated to only being an application, it does not contain code.

Define an Application Project

Create a new project from the [[empty]](#empty) template:

com.example.application

In this project, create a file called application.bndrun. Open it, and go to the Run tab.

We now have to establish what needs to be a part of the application. For this example, we drag the following bundles to the Initial Requirements list.

org.apache.felix.gogo.command

org.apache.felix.gogo.shell

com.example.eval.simple.provider

Select a Resolve mode of auto and then click the Debug OSGi to see if the application works.

____________________________

Welcome to Apache Felix Gogo

g! eval 3+5

8.0

g!

Executable JAR

To deploy the application we need a file in a deployable format. One of the formats supported by bndrun files is the executable JAR. This format packs a framework and all necessary bundles in a single JAR file. You can export this by adding the following in the bnd.bnd file in the com.example.application project.

-dependson *

-fixupmessages The JAR is empty

-export application.bndrun

This will tell bnd to create an executable JAR whenever something changes. (The -dependson * makes sure that this is the last project built so that the dependencies are ready when we export them to the executable JAR.)

If you open the target directory in a shell, you now see a file application.bndrun.jar. This file can directly be run from the command line.

$ cd com.example/com.application.playground

$ java -jar target/application.bndrun.jar

g! simple:eval 3+7

10

g!

Docker Image

Executable JARs are perfect for a Docker image.

FROM java:8-jdk-alpine

ADD target/application.bndrun.jar /

WORKDIR /data

ENTRYPOINT ["java", "-jar", "/application.bndrun.jar"]

You can now build the docker image and run it.

$ docker build .

Sending build context to Docker daemon 6.456MB

Step 1/4 : FROM ggtools/java8

---> f8f0aa8056f4

Step 2/4 : MAINTAINER pkriens@gmail.com

---> Using cache

---> 0e918347c1f3

Step 3/4 : CMD java -jar application.bndrun.jar

---> Using cache

---> 9f16d98f80ca

Step 4/4 : ADD target/application.bndrun.jar application.bndrun.jar

---> b1559881a6eb

Successfully built b1559881a6eb

$ docker run -i b1559881a6eb

____________________________

Welcome to Apache Felix Gogo

g! rhino:eval 41+1

42.0

g!

Summary

In this chapter we learned about the concept of executable JARs: JARs that contain the OSGi framework and all necessary bundles. We then looked at how to build such a JAR and used it to create a Docker image.

Gradle

TL;DR

If you are a user of a bnd workspace and there is build master that maintains the low level details then you can skip this section. This is only for build masters.

Bndtools uses Gradle as the continuous integration build tool. Every bnd workspace can automatically be built by Gradle using straight generic templates. The output of this build is identical to the artifacts built in Eclipse or Intellij.

The templates use gradlew, which is a small script that fetches the correct version of Gradle. You can start a build typing ./gradlew clean build, getting a list of the tasks is ./gradlew tasks.

You may also want to look at Gradle Integration

Gradle Setup

The workspace template that was used in an earlier session provided a bnd workspace to Bndtools. However, it also included setup for Gradle. Gradle is one of the primary build tools, nowadays competing with maven for primacy. The main difference is that Maven is very declarative while Gradle allows fine-grained control using the Groovy or Kotlin language.

This makes it possible to build all the bundles in the workspace, and the application, via the command-line. The primary purpose of this is to build the artifacts on a different system than the developer’s. Before continuous integration on external servers was the norm, many projects found that the application worked on one developer’s machine but not necessarily on another due to a difference in configuration.

Building

The workspace is set up to build all projects in the workspace directory using the Gradle bnd plugin. This plugin takes the bnd files and tells Gradle how to compile and build the artifacts.

Therefore, to build the workspace, you can do the following:

$ cd com.example

$ ./gradlew clean build

.....

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 4s

13 actionable tasks: 13 executed

The bnd Gradle plugin will build exactly the same artifacts as the Eclipse IDE.

Lets try out how the application runs.

$ java -jar com.example.application/target/application.bndrun.jar

____________________________

Welcome to Apache Felix Gogo

g! eval 41+1

42.0

Gradle Tidbits

-

There is no need to install Gradle. The workspace template contains two script (

gradlewfor MacOS & Linux, andgradlew.batfor Windows) that will download an appropriate Gradle executable. -

You can find out the tasks you can run with

./gradlew tasks -

By default, Gradle compiles in the same directory as Eclipse/Intellij. This means that they can sometimes override each other’s files. This is only a problem if you build locally with Gradle, which is generally not necessary. If Eclipse is confused, it is likely a Gradle build that destroyed its files.

Using Gradle

The default workspace build with Gradle is driven by the bnd configuration files. Since bnd also runs inside Eclipse and Intellij, there is no need for special Gradle configuration. However, there are situations where you need to generate sources or run some special Gradle plugin. For this reason, each project directory can have a build.gradle file that extends the Gradle setup. This can be a lifesaver. However, these gradle files are not run inside the IDE. It is therefore recommended to limit the use of this facility to cases when there is no bnd solution.

When to Use

The primary purpose of Gradle is to do the CI build on a remote server. However, I’ve noticed that a lot of developers do local builds with Gradle, often from the distrust that the CI build might not be the same. The bnd team sees any discrepancy between the Eclipse IDE and the Gradle build as a high priority error and thus they are rare. Trust Eclipse …

Git

TL;DR

If you have a build master that sets up the workspace for you then this section unnecessary for you. The following sections are only intended for people that need to maintain workspaces.

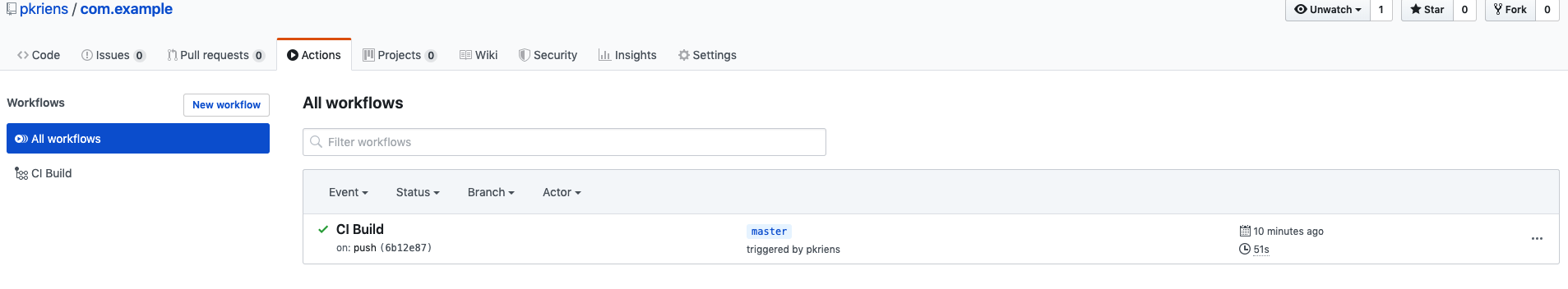

Currently the workspace is local on our laptop. Today, by far the most widespread solution for a Source Control Management System (SCMS) is Git. In this section we’ll connect the com.example workspace to Github and use the Github continuous integration servers (Github Actions) to build it.

You may also want to look at Github & Actions.