About Modularity

Software Complexity

The problem that OSGi solves is the key problem of software engineering: How to keep the complexity of large systems under control. Every developer knows the dreaded feeling if an unchecked software system becomes a bloating monster where every new functions becomes more and more expensive to add. OSGi addresses this problem with modularity combined with the magic sauce of services.

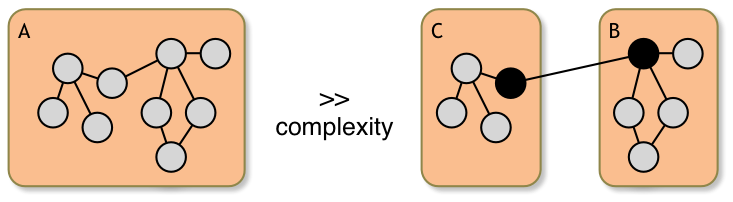

Software complexity grows exponentially with the number of links inside the code base. (Where a link is a line of code calling a method or using a field.) Complexity grows exponential with the number of these links. Therefore even a small reduction of links has significant impact on the complexity of large systems. If you have a module with n internal links and you can perfectly separate it in to two equal sized modules that each have half the links then each module has much less complexity than half the complexity of the original module. The following picture illustrates this modularity effect.

If module A has 9 links then its complexity is proportional to 92 which is 81. Module B and C together are 32 + 62 which is 45 and even in this simplistic example almost halved! The numbers are just to illustrate the mechanism, the actual complexity is harder to estimate. However, the gain in reality is much higher because the number of links in even moderately sized programs is magnitudes higher.

Modularization therefore reduces complexity because it reduces the number of links that are available from any point by enforcing a private and a public world for each module. Any line of code can now only refer to its own (private) space and the public world. Without modularity, the developers could also link to anywhere in the code base. (And they will.) In the previous picture the private objects were depicted grey as is usually in the OSGi specifications. Black is used for public and white is used for imports.

Cohesion

The seminal paper from Parnas that first mentioned software modularity was called “On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules”. The paper’s insight was that there was a tremendous difference in flexibility based on how the system was decomposed into modules. Some decompositions required major changes for even small new requirements, other decompositions could incorporate new requirements with minimal change.

An important concept in Parnas’ paper is the concept of change. Large software systems evolve over time at an often surprising rate. It is therefore paramount that we’re not only minimizing the number of links, but that we also make those links between modules as resilient as possible to change. The relevant concept here is cohesion. Things that are closely related should be close together in the private space of the module. Things that are not cohesive should be in separate modules.

The reason that cohesion is so important is that they define things that are inseperable and will therefore evolve together. Things that evolve at a different rate and/or could be used separately should not be in the same module.

Within a private space private things are unknown to the rest of the world. Removing that private thing cannot affect anybody but the local residents. For example, removing a private class from a package is invisible to any external module. Anything that is not public can be changed at will. This clearly implies that by minimizing the public parts we keep our options open for the inevitable changes.

Not All Links Are Equal

So far this view of modularity is widely shared in our industry. However, this view ignores the quality of the link. not all links are created equal. Some links cause a long train of transitive dependencies, other links link are to very volatile constructs. These types of links might still make it very hard to evolve a large software system because small new requirements still introduce system wide changes.

This lesson was learned the hard way in the nineties when object oriented programming came of age. The theory of objects was that you could reuse the classes from one system into the next system. However, the practice was that the transitive dependencies between the classes caused almost perfect connectivity from any class in the system to any other class. Trying to use a single classes often resulted in dragging in the whole of the previous system. The sad story was that most of the time the classes were designed to be reusable and had a restricted API. However, the only way to use this API was to have a hard reference to an implementation class that dragged in a lot of baggage unrelated to the reusable API.

A part of the solution came with interfaces in Java. Interfaces were the emergency break on transitive dependencies. You could now specify an API contract without creating a link to a concrete class. Instead of code depending on implementations, the model turned into both code and implementations depending on a middle man: the interface. This model allowed us to substitute different implementations depending on the needs. This gave a boon to our industry. Suddenly our code was much easier to test and it became a lot easier to build systems out of separately developed components.

The ideal link therefore allows modules to collaborate but it does not constrain any one of them by having implementation dependencies. All participants in the collaboration are free to seek their own implementations and private choices. So the holy grail of modularity is to turn you gigantic trees of code links into tiny little toothpicks. Meet OSGi.

Next